Castell Dinas Bran, Denbighshire, Wales

- Michael Smith

- Feb 20, 2020

- 6 min read

Castell Dinas Bran, nestling above the River Dee and the town of Llangollen, is one of the most evocative ruins in Wales. Perched on a hill, one thousand feet above the valley floor, its shattered walls and ruined arches make it one of the most dramatic mediaeval ruins in the whole of Wales.

History and construction of Castell Dinas Bran

Although much ruined, the castle shows several periods of construction, the first of which appears to have been as an Iron Age hill fort; the top of the hill forming a ditched D-shape enclosure measuring approximately 600 x 350 feet. However, the enclosure may be later; possibly even a mediaeval outer bailey.

In the northwest corner of this enclosure, a sheer-sided mediaeval rock-cut ditch to south and east creates a stout protection for the castle which survives within it. To the north, both castle and enclosure are defended by the precipitous cliffs of the hilltop as it faces towards the Trefor ridge.

The mediaeval castle is thought to have been built in the 1270s on the site of a twelfth century timber castle or palace erected by the princes of Powys Fadog. It is believed that the castle we can see today was built by Gruffydd ap Madog, whose father built the nearby Valle Crucis Abbey.

Following the invasion of Wales by Edward I in 1277, the occupants set fire to the castle rather than surrender it to a force led by Henry de Lacy. Despite this, the castle was not sufficiently damaged to be unusable and a garrison was stationed there.

However, although it was granted to John de Warrene following the death of the Welsh prince, Llewelyn ap Gruffydd in 1282, it was abandoned in favour of John’s new castle at Holt, further downstream towards Chester. Dinas Bran itself was then to fade into obscurity, known more now for its spectacular location high above the town than as a fortress of rebellion.

Plan of the castle

Dinas Bran is not a sophisticated building and, in common with many “native” Welsh castles, its general plan is irregular. Yet it was clearly an aspirational building and contains a number of advanced architectural features.

The castle takes the form of a rectangular enclosure, measuring approximately 250 x 100’, protected to the south and east by an impressive rock-cut ditch. At its eastern end, the main point of access and the part of the castle most intended to impress, it is graced by a large keep flanked by a twin-towered gatehouse, giving access to the main courtyard.

To the south was a large hall – apparently with grand windows – and a D-shaped tower; to the west was a suite of outbuildings. The keep appears to have been protected on the inside by another rock-cut ditch although this may, like that at Degannwy, also have served as a quarry for building materials.

Description of the ruins:

The ditch

The most substantial part of what remains of Dinas Bran is its impressive rock-cut ditch. At least twenty feet deep, it is precisely hewn; in particular at its south east corner where it is turns through 90 degrees towards the north. This ditch was most likely the source quarry for the main castle buildings, of which the keep and gatehouse are the core survivors.

The ditch is less pronounced on the western side where it appears to be a continuation of the earthwork enclosure; there is no requirement on the north side, where the drop is precipitous.

Keep

The keep may originally have been rectangular, in the manner of those at Dolwyddelan or at Dinas Emrys. However, its eastern and northern walls have largely disappeared, possibly forming the debris pile in the ditch which today enables the visitor to gain access to the courtyard.

Another possibility is that it was aspsidal, in the manner of that at Ewloe in Flintshire. Irrespective of its shape, it is likely to have once comprised a basement, first floor accommodation and a possible third storey which, like Ewloe, protected the roof space.

The keep seems to have been built separately to the rest of the castle. There is a curious passageway running between it and a neighbouring wall to its west which joins with the gatehouse. This may have formed a defensive barrier to the keep entrance at first floor level, crossed by a drawbridge. To the west, beyond this wall, is the quarried out pit (mentioned above) which some have interpreted as an inner defensive ditch to the keep.

Gatehouse

The gatehouse is a particularly advanced feature of the castle, comprising two narrow drum towers protecting an equally narrow entrance. The southernmost tower still retains its barrel-vaulted ceiling and recent consolidation work has replicated some surviving quoin work (this chamber cannot be accessed but is clearly visible through iron-barred doorways). The northern tower does not survive to a great height but its plan is easy to see.

What is curious is the narrowness of both towers and the entrance. The building was clearly constructed at some expense (surviving mouldings suggest door jambs and a vaulted ceiling) but the practicality of the entrance is a matter for debate.

Had the “Iron Age” enclosure indeed been the main bailey for the castle, it is possible the gatehouse was built largely as a show of wealth and prestige and used for access by foot only, horses and carriages remaining in the outer bailey.

In its complexity of design, the gatehouse is reminiscent of the much more majestic gatehouse at Cricieth on the Llyn. In both cases, the requirement for such a building on top of a hill seems singular.

Similarly, it is not clear how the ditch was originally crossed in order to reach the gatehouse. The debris within the ditch at the eastern end may conceal the remains of a bridge or, if such a bridge was originally wooden, perhaps the footings for the stone piers which supported it.

Hall and D-shaped tower

For most visitors, the remains of the southern wall of the hall with its two “windows” are the defining feature of the remains of the castle. Whether these openings were indeed windows or (as seems likely given the exposure of the site) originally much narrower openings, they nonetheless define a building of status.

Seen from any angle below, the hall would have shown the wealth of the owners and confirmed the building’s position as a building of status. With the neighbouring D-shaped tower, perhaps 30-40 feet high, this southern wall complex would have appeared as both impressive and welcoming: a palace fit for a local prince.

Courtyard

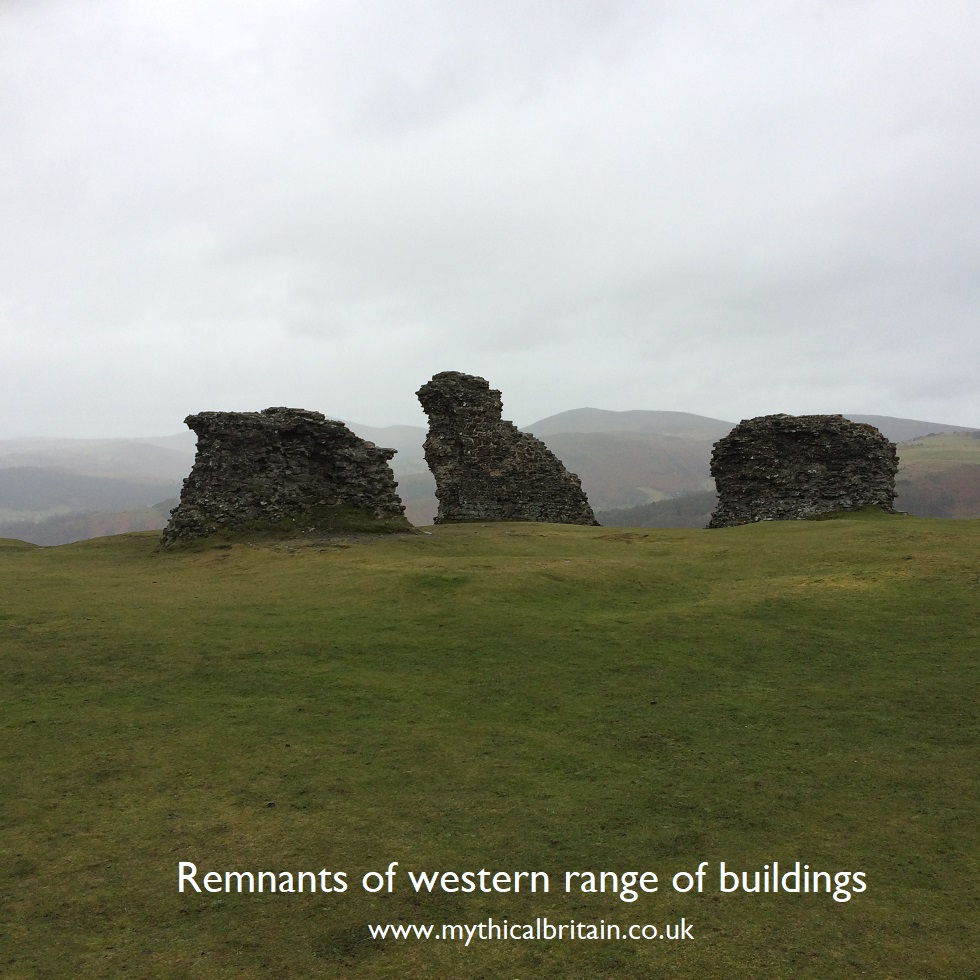

The remainder of the courtyard reveals little of its secrets to the modern traveller although a postern gate into the great ditch via the south wall is still visible. It is thought the western end of the courtyard would probably have comprised kitchens and service quarters for the castle although the evidence - above ground at least – is limited.

A castle to inspire

Although much derelict today, Castell Dinas Bran still achieves its original purpose: to inspire as a castle in the landscape.

No photograph from any angle can quite do justice to the view when first seen by the visitor from below, especially from the A5 when approaching Llangollen towards England and with the castle on the traveller’s left. It appears almost to soar in the air atop its lofty crag, stating still the power of the princes of Powys Fadog all those centuries ago.

Certainly it has inspired me in my own printmaking activities; one of the linocut prints of which I am most proud is that of Dinas Bran in the Snow (see left; available to buy here).

This castle through the centuries has survived whatever the weather can throw at it; now, recently consolidated by Cadw and others, it stands resilient again – once more to sing the ancient songs of the Welsh atop the wind-blown ridges.

.

Further Information

Coflein listing for Dinas Bran Castle here

Coflein listing for Dinas Bran outer enclosure here

Page for Dinas Bran on Castles of Wales website (some super photographs) here

About the author

Michael Smith read history at the University of York and is an historian, printmaker and translator of fourteenth century Middle English poetry.

His illustrated translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was published by Unbound in 2018. He is currently translating (and illustrating) the Alliterative Morte Arthure, a poem written during the time of Richard II and Henry Bolingbroke, which publishes in September 2020.

You can support this book (jacket shown above) and have your name printed in the back as a named patron here

Slide show of photographs of Castell Dinas Bran

(click the arrow to taken to different images)

留言